American playwrights are mostly itinerant workers. We have a piece done here…another one there…maybe someone gives a play we wrote a second production and we get a chance to see it in a different light. Or it gets a whole lot of readings in a bunch of places because putting on readings series is a way theaters can show they support new work (insert ironic quotations where you feel appropriate).

In the checkerboard journey, it’s not often that a playwright can take a step back and get a sense of her work in one place and time.

It’s not within the capacity (or interest) of most theaters to devote an entire season to one playwright’s work. But when they do (and hooray for Signature Theater for making it their mission) is to allow a playwright’s work to be put into an order and context and in such close proximity to itself that you can get an idea of the arc of his or her career, and what ideas they’ve continued to explore, and which ones they’ve worked through, and see the breakthoughs, and see what led up to them.

Some years ago, I saw Jason Robards & Colleen Dewhurst led a huge cast in an alternating repertory of O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey” and “Ah! Wilderness.” I saw them back-to-back, and the contrast between the wished-for family and the dark portrait of the one he had was both memorable and heartbreaking.

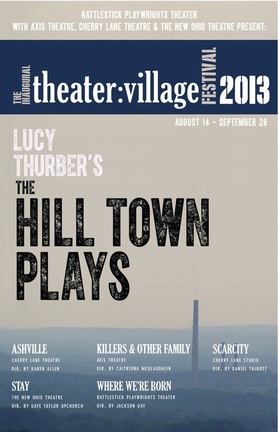

So it was with great interest I read about Rattlestick Theater's plan to produce the 5-play Hill Town cycle by Lucy Thurber. They committed a huge amount of time, effort, money, talent and what I am sure were unbelievably profound & complicated logistics to a body of work from a playwright who is hitting the meat of her career.

So I bought my tickets (for a reasonable price, which showed they were serious about making it easy to see all of them), and sat down with my calendar. I saw the first 4 plays in about a 5-day stretch just after they started previewing, and the fifth last Sunday, and then “Killers & Other Family” again this week.

I saw most of the plays fairly early in previews, which is when your theater friends say: “…come later, when we’re on our feet.” I like seeing the play come to life early on, and things people are still trying, before the performances get set, and maybe (for example) the door comes off the refrigerator and everyone has to deal with that along with remembering their lines and blocking.

Each play, on its own, is worth seeing and can stand alone, but the power of all 5 together creates a kind of power and urgency that is many-faceted: you can’t divide the characters and their emotional lives from the place they come from, and a line or an action, or even a piece of food reverberates starts out in one play, is repeated in another, turns up again later on, depicted from a different distance, someone else’s point of view, as a symbol of something that was once important, and is now ordinary.

You must understand that along with being a playwright, I am a theater geek, a nerd, a theater lover. I go to shows more than once if I really like them, and I almost always come away from plays, even the awful ones, with something to turn over in my mind on the way home: a moment, an actor I didn’t know before, a phrase or a theme that I can put in my collection.

I’d seen three of the plays before in earlier versions/productions, as well as Thurber’s epic, “Monstrosity,” at 13P (which never would have been put on by a traditional theater, only one which made its playwrights its artistic directors) and the idea that I could see all of the plays in a short time, in order, seemed to me one of the most interesting things happening in American theater this season.

One of the reasons I like her work is that Thurber writes about class in America, often from the point of view of the working (and non-working) poor. She doesn’t make fun of her characters, or look down on them, or make them into stereotypes or caricatures, and she writes a lot of them, which few enough playwrights do in mainstream theater these days (and fewer women).

Thurber persists in writing about the financially, emotionally and spiritually poor: her people often drink and drug because they’ve long since lost the ability to dream, and whose response to something unexpected or frightening is frequently violent. They can be dangerous one moment, loving the next, or both at the same time to a degree that whoever comes out of that environment can never completely leave it behind.

(In "Monstrosity," a dystopian play with a cast of dozens, Thurber depicted an army of have-nots, led by a woman, conducting a guerilla war against a brutal regime, which pitted her against her own brother, and which showed how violence inevitably changes the people who first encounter it then embrace it).

"Scarcity."

"Scarcity." The Hill Town plays tell the journey of a girl over the course of some two decades. She’s called Rachel in the first and last plays, and also called Celia and Lizzie and Lilly. She has a brother called Billy, and depending on which play, a boyfriend named Jake, a cousin named Tony; Danny and Jeff are the brother and boyfriend she left behind on her journey. The men can be both protective and destructive. They want to take care of her, but they also want to own her. She does what she has to in order to survive, to keep them from hurting her, and to get them to protect her. Her body, her looks, her intellect are her currency, and she trades it for safety, or at least an escape from pain.

Brother Billy, who leaves in the first play, promises to come back for Rachel, and in the last play, he does, when both of them have broken away from the country town in western Massachusetts where they grew up, and managed to educate themselves, but still keep running into what they can’t leave behind.

The plays are character-driven, but the way the world is going pushes them one way and another. In, “Scarcity,” the first play, the mother, played by the exquisite Didi O’Connell works at the mall and cries a lot. Her face shows all the sadness of her life, and a dogged determination to somehow keep going. The father (Gordon Joseph Weiss) doesn’t work (except for an occasional logging job). Mostly he drinks. A man tells a woman to get him a beer within the first five minutes of four of these plays. They drink Rolling Rock and Bud Light and whiskey from the bottle.

Their offspring are dependent on the erratic pair, though Billy (Will Pullen) is almost of an age to make a break for it. The play is set in 1992 (before welfare was “reformed”), so they do have food stamps. Not really enough to feed the family…but a cousin, who’s a cop, brings them groceries, even steak (though nothing comes without a price).

It’s also a time when there’s a good public school that gives Billy a chance to use his considerable intelligence, attracting the attention of one of his teachers. She’s a born do-gooder, whose thesis was about poverty in America. Billy both needs her to escape, and can’t stand it when she commits the unforgivable sin of reminding him of his poverty. Rachel is too young to escape with Billy, and at the end, she knows she’s going to have to find her own way out.

It’s a slightly different set of circumstances in “Ashville,” set in 1997, in which Celia, who’s a high school sophomore, lives with her mother (there’s no father in sight), and has a boyfriend, Jake, who stays overnight, and drives her to school, and sometimes keeps her mother’s boyfriends from pawing her. Jake’s cousin Joey hasn’t quite given up yet. He’s got a girlfriend, Amanda, that he’s crazy about. And they all hang out with the drug dealer next door, who plays his vinyl and talks about James Joyce, and proclaims himself a genius when he’s stoned. When Jake proposes to Celia, she knows this isn’t the way she needs to get out of the house, and tries to find a way to articulate it all to Amanda, who listens to her, and notices that she’s wearing new jeans. Celia’s attracted to Amanda, adding yet another layer of danger to it all.

We’re in the new millennium, 2002, for “Where We’re Born,” in which Lilly returns to her hometown from her first semester in college. Her cousin Vin, who always looked out for her, lets her stay with him and his girlfriend Franky (who loves the jeans she’s wearing) because there’s no way she can stay with her mother. Vin’s buddies, Drew and Tony, drink and smoke with him, talk about getting laid, and don’t realize it as they make their world smaller and smaller. They are afraid of the “other”: immigrants and blacks and people who are different. They are mostly underemployed, except for some occasional logging gigs. A year or so later, they’d be talking about signing up for the military. In 2002, they’re creating a rhetoric that’s in full bloom today, driving a wedge between the classes, the races, Americans. At the start of the play, Lilly has just crossed to the other side by going away to college (where she stuns Vin with the fact that books cost “like $75"). In the town where she was born, she finds herself drawn to Franky, and it leads to an outcome in which her bridges are burned, and she can’t ever come back.

Lizzie lives in New York City in 2009, when “Killers and Other Family” takes place. She’s working on her thesis (about poverty in America, after which, she will be an “authority”), which is due in two weeks. When her brother and ex arrive, Lizzie quickly finds out just how thin her veneer of civility and scholarship is. It’s sad, and ugly and raucous to see these two invaders vandalizing the world Lizzie’s made for herself. And ultimately, Lizzie has to choose between family and the man who loved her and abused her and her current lover.

Rachel is teaching at a liberal arts college in 2013 in the cycle's final play, "Stay." Her book of short stories, inspired by her own family, has made her name. Her novel is due in two weeks. Her drive and talent and survival skills have manifested as an alter ego/angel who supports her, warns her, and gives her advice. (In other words, she’s a writer). Rachel is alone and stuck, and seems to have stopped feeling. Billy, also grown up, and a lawyer, arrives on the scene, and serves her steak, and brings her a beer. Something has changed…and some things have not.

The play ascends into fugues of magical realism, and they are earned. Billy and Rachel have to deal with the hard truths (and answering machine messages from their mother, still played by O’Connell), that they are both damaged people, damaged in a very specific way by their upbringing, as well as their ambition, and they are at a breaking point. The angel/alter ego gives Rachel an instruction when she most needs it, and while we don’t see what will happen, we might feel that there has been a change, that a cycle has been broken, that the broken might become whole.

It’s an Adventure

My own alter ego is telling me to go to bed now, because it’s late and I have to be at work tomorrow. I have two plays going up between now and mid-October, and both have logistics issues that need to be addressed. I do not know where or when my next production after that is. I need to make sure I get my stuff out there. There are only so many slots in a season, only so many theaters.

My angel is also telling me that it’s good and important for us – the audience, the theater lovers, the Americans – to see the complete story Lucy Thurber set out to tell. Who better to tell it? And who better than us to bear witness?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed