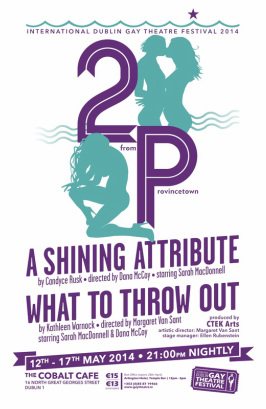

I'll be posting regularly and linking to it here, if you care to follow the new adventures of EAT...I mean CTEK Arts...as we head North of the Liffey for another opening, another show in Dublin.

|

And to my annually updated Ireland blog, which you can find here.

I'll be posting regularly and linking to it here, if you care to follow the new adventures of EAT...I mean CTEK Arts...as we head North of the Liffey for another opening, another show in Dublin.

0 Comments

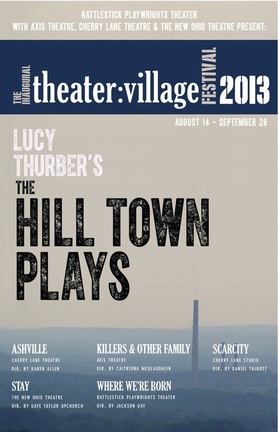

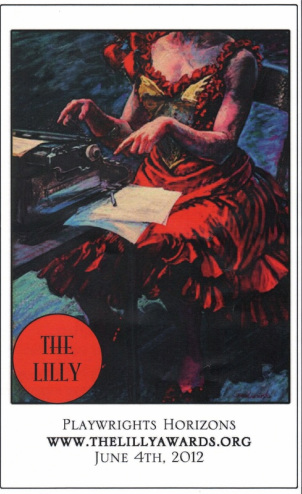

The Audacity of Repertory American playwrights are mostly itinerant workers. We have a piece done here…another one there…maybe someone gives a play we wrote a second production and we get a chance to see it in a different light. Or it gets a whole lot of readings in a bunch of places because putting on readings series is a way theaters can show they support new work (insert ironic quotations where you feel appropriate). In the checkerboard journey, it’s not often that a playwright can take a step back and get a sense of her work in one place and time. It’s not within the capacity (or interest) of most theaters to devote an entire season to one playwright’s work. But when they do (and hooray for Signature Theater for making it their mission) is to allow a playwright’s work to be put into an order and context and in such close proximity to itself that you can get an idea of the arc of his or her career, and what ideas they’ve continued to explore, and which ones they’ve worked through, and see the breakthoughs, and see what led up to them. Some years ago, I saw Jason Robards & Colleen Dewhurst led a huge cast in an alternating repertory of O’Neill’s “Long Day’s Journey” and “Ah! Wilderness.” I saw them back-to-back, and the contrast between the wished-for family and the dark portrait of the one he had was both memorable and heartbreaking. So it was with great interest I read about Rattlestick Theater's plan to produce the 5-play Hill Town cycle by Lucy Thurber. They committed a huge amount of time, effort, money, talent and what I am sure were unbelievably profound & complicated logistics to a body of work from a playwright who is hitting the meat of her career. So I bought my tickets (for a reasonable price, which showed they were serious about making it easy to see all of them), and sat down with my calendar. I saw the first 4 plays in about a 5-day stretch just after they started previewing, and the fifth last Sunday, and then “Killers & Other Family” again this week. I saw most of the plays fairly early in previews, which is when your theater friends say: “…come later, when we’re on our feet.” I like seeing the play come to life early on, and things people are still trying, before the performances get set, and maybe (for example) the door comes off the refrigerator and everyone has to deal with that along with remembering their lines and blocking. Each play, on its own, is worth seeing and can stand alone, but the power of all 5 together creates a kind of power and urgency that is many-faceted: you can’t divide the characters and their emotional lives from the place they come from, and a line or an action, or even a piece of food reverberates starts out in one play, is repeated in another, turns up again later on, depicted from a different distance, someone else’s point of view, as a symbol of something that was once important, and is now ordinary. You must understand that along with being a playwright, I am a theater geek, a nerd, a theater lover. I go to shows more than once if I really like them, and I almost always come away from plays, even the awful ones, with something to turn over in my mind on the way home: a moment, an actor I didn’t know before, a phrase or a theme that I can put in my collection. I’d seen three of the plays before in earlier versions/productions, as well as Thurber’s epic, “Monstrosity,” at 13P (which never would have been put on by a traditional theater, only one which made its playwrights its artistic directors) and the idea that I could see all of the plays in a short time, in order, seemed to me one of the most interesting things happening in American theater this season.  Why This is Important One of the reasons I like her work is that Thurber writes about class in America, often from the point of view of the working (and non-working) poor. She doesn’t make fun of her characters, or look down on them, or make them into stereotypes or caricatures, and she writes a lot of them, which few enough playwrights do in mainstream theater these days (and fewer women). Thurber persists in writing about the financially, emotionally and spiritually poor: her people often drink and drug because they’ve long since lost the ability to dream, and whose response to something unexpected or frightening is frequently violent. They can be dangerous one moment, loving the next, or both at the same time to a degree that whoever comes out of that environment can never completely leave it behind. (In "Monstrosity," a dystopian play with a cast of dozens, Thurber depicted an army of have-nots, led by a woman, conducting a guerilla war against a brutal regime, which pitted her against her own brother, and which showed how violence inevitably changes the people who first encounter it then embrace it).  "Scarcity." "Scarcity." Now That’s a Narrative Arc! The Hill Town plays tell the journey of a girl over the course of some two decades. She’s called Rachel in the first and last plays, and also called Celia and Lizzie and Lilly. She has a brother called Billy, and depending on which play, a boyfriend named Jake, a cousin named Tony; Danny and Jeff are the brother and boyfriend she left behind on her journey. The men can be both protective and destructive. They want to take care of her, but they also want to own her. She does what she has to in order to survive, to keep them from hurting her, and to get them to protect her. Her body, her looks, her intellect are her currency, and she trades it for safety, or at least an escape from pain. Brother Billy, who leaves in the first play, promises to come back for Rachel, and in the last play, he does, when both of them have broken away from the country town in western Massachusetts where they grew up, and managed to educate themselves, but still keep running into what they can’t leave behind. The plays are character-driven, but the way the world is going pushes them one way and another. In, “Scarcity,” the first play, the mother, played by the exquisite Didi O’Connell works at the mall and cries a lot. Her face shows all the sadness of her life, and a dogged determination to somehow keep going. The father (Gordon Joseph Weiss) doesn’t work (except for an occasional logging job). Mostly he drinks. A man tells a woman to get him a beer within the first five minutes of four of these plays. They drink Rolling Rock and Bud Light and whiskey from the bottle. Their offspring are dependent on the erratic pair, though Billy (Will Pullen) is almost of an age to make a break for it. The play is set in 1992 (before welfare was “reformed”), so they do have food stamps. Not really enough to feed the family…but a cousin, who’s a cop, brings them groceries, even steak (though nothing comes without a price). It’s also a time when there’s a good public school that gives Billy a chance to use his considerable intelligence, attracting the attention of one of his teachers. She’s a born do-gooder, whose thesis was about poverty in America. Billy both needs her to escape, and can’t stand it when she commits the unforgivable sin of reminding him of his poverty. Rachel is too young to escape with Billy, and at the end, she knows she’s going to have to find her own way out. It’s a slightly different set of circumstances in “Ashville,” set in 1997, in which Celia, who’s a high school sophomore, lives with her mother (there’s no father in sight), and has a boyfriend, Jake, who stays overnight, and drives her to school, and sometimes keeps her mother’s boyfriends from pawing her. Jake’s cousin Joey hasn’t quite given up yet. He’s got a girlfriend, Amanda, that he’s crazy about. And they all hang out with the drug dealer next door, who plays his vinyl and talks about James Joyce, and proclaims himself a genius when he’s stoned. When Jake proposes to Celia, she knows this isn’t the way she needs to get out of the house, and tries to find a way to articulate it all to Amanda, who listens to her, and notices that she’s wearing new jeans. Celia’s attracted to Amanda, adding yet another layer of danger to it all. We’re in the new millennium, 2002, for “Where We’re Born,” in which Lilly returns to her hometown from her first semester in college. Her cousin Vin, who always looked out for her, lets her stay with him and his girlfriend Franky (who loves the jeans she’s wearing) because there’s no way she can stay with her mother. Vin’s buddies, Drew and Tony, drink and smoke with him, talk about getting laid, and don’t realize it as they make their world smaller and smaller. They are afraid of the “other”: immigrants and blacks and people who are different. They are mostly underemployed, except for some occasional logging gigs. A year or so later, they’d be talking about signing up for the military. In 2002, they’re creating a rhetoric that’s in full bloom today, driving a wedge between the classes, the races, Americans. At the start of the play, Lilly has just crossed to the other side by going away to college (where she stuns Vin with the fact that books cost “like $75"). In the town where she was born, she finds herself drawn to Franky, and it leads to an outcome in which her bridges are burned, and she can’t ever come back. Lizzie lives in New York City in 2009, when “Killers and Other Family” takes place. She’s working on her thesis (about poverty in America, after which, she will be an “authority”), which is due in two weeks. When her brother and ex arrive, Lizzie quickly finds out just how thin her veneer of civility and scholarship is. It’s sad, and ugly and raucous to see these two invaders vandalizing the world Lizzie’s made for herself. And ultimately, Lizzie has to choose between family and the man who loved her and abused her and her current lover. Rachel is teaching at a liberal arts college in 2013 in the cycle's final play, "Stay." Her book of short stories, inspired by her own family, has made her name. Her novel is due in two weeks. Her drive and talent and survival skills have manifested as an alter ego/angel who supports her, warns her, and gives her advice. (In other words, she’s a writer). Rachel is alone and stuck, and seems to have stopped feeling. Billy, also grown up, and a lawyer, arrives on the scene, and serves her steak, and brings her a beer. Something has changed…and some things have not. The play ascends into fugues of magical realism, and they are earned. Billy and Rachel have to deal with the hard truths (and answering machine messages from their mother, still played by O’Connell), that they are both damaged people, damaged in a very specific way by their upbringing, as well as their ambition, and they are at a breaking point. The angel/alter ego gives Rachel an instruction when she most needs it, and while we don’t see what will happen, we might feel that there has been a change, that a cycle has been broken, that the broken might become whole.  It’s Not Just a Job, It’s an Adventure My own alter ego is telling me to go to bed now, because it’s late and I have to be at work tomorrow. I have two plays going up between now and mid-October, and both have logistics issues that need to be addressed. I do not know where or when my next production after that is. I need to make sure I get my stuff out there. There are only so many slots in a season, only so many theaters. My angel is also telling me that it’s good and important for us – the audience, the theater lovers, the Americans – to see the complete story Lucy Thurber set out to tell. Who better to tell it? And who better than us to bear witness? I’m not entirely opposed to aging. As artists, for example, I think as our eyesight goes, our vision gets stronger. I feel as though there’s more room for memory, resonance, a greater palette of emotions that we can draw on when we write or see a play after a lifetime of taking a seat and waiting for the lights to go down. The colors are richer, deeper, the music more complex (and if you wore earplugs, you still have your hearing). When I was beginning in the theater, I’d go see a play as many times as I could (the only option in a town with a more limited theater scene than NYC). If I could get hold of a copy of a script, I’d read it and practically commit it to memory. Before I realized there were such things as writing workshops, I tried to take apart the scripts and see how they worked and figure out why the artist chose to do it just that way. All of this was part of my coming out…as an artist. I’m starting this on a bus heading down the Jersey Turnpike (on Pride Sunday, no less) on my way to see the last performance of a run of my play, “Grieving for Genevieve,” at the Venus Theater in Laurel, MD. The last time I missed a Pride Sunday in NYC was to see a reading of my play, “Grieving for Genevieve” in Chicago.  It’s been a wonderful month, indeed a wonderful year, for my theater life. I’ve had shows produced, I’ve seen some great shows, and it’s all just as alive to me and essential as it was when I was 24 and living in a tiny room at the Baptist Women’s Residence and second-acting the show every night at Mirror Rep. Though I do have a better apartment now. The sense memories came back strong last Monday when I went to see Tennessee Williams’s “The Two Character Play.” I’d been hoping to see it, both because it’s rarely been revived, as well as wanting to see Amanda Plummer onstage again. The first time I saw Plummer’s work was in “Agnes of God,” on Broadway, with her, Elizabeth Ashley and Geraldine Page. (I’ve written about that before...it was a “come to Jesus” moment). Even though I hadn’t seen a lot, I knew enough to realize that I was in the presence of three great actresses. Leafing through the playbill at “The Two Character Play,” I realized I’ve seen Amanda Plummer in most of her New York City appearances, from Glass Menagerie to Pygmalion. I think one of the reasons that at the end of his life, when Tennessee Williams went out of fashion, when it was okay for the intelligentsia to make fun of him and his work, to dismiss it, is at least partially because of a level of homophobia that was acceptable back then, and even now can be heard as an undertone if you listen carefully. If you read Christopher Bram’s wonderful book “Eminent Outlaws,” he traces a similar trajectory in Edward Albee’s reputation, in the reception of “Virginia Woolf” both before and after it was widely known the author was a gay man. Frank Rich can write elegiacally about his surrogate gay parent in New York magazine, but fairies were always fair game for theater critics. So it’s good to see him having a renaissance in that people are going back to the work and saying: hey, this is worth bringing back. These are things people need to hear again, and know again. When the play began, I heard Tennessee’s voice, strong & rich, and in different ways than in his earlier plays (probably the biggest critique that any writer faces: that This One is not The Same as the Last One). Along with his unique voice and ideas, I saw shadows of Beckett & Ionesco, and the artist wrestling with himself. As always, there was the shadow of his sister. We all have something we try to write, and write out, and there it is. I saw how Williams’s language has informed so much of American theater. Without Williams creating a voice in American theater, you’ve got…Miller (I will qualify this by saying “Post WWII mainstream theater in America”). Which is a much more judgmental place. I also realized the influence that Amanda Plummer has had on so many actors…they don’t have her mercurial quality, the way her voice does things, but they have taken cues from her unique style & energy. Brad Dourif more than held his own as her brother/foil/director/scene partner. I read Hilton Als’s critique in the New Yorker, and he felt that Dourif and the direction were not up to par with Plummer & Williams. I disagree, at least about Dourif (the lighting was too dark for me). Though I would like to see David Hyde Pierce take a shot at that part. (I’d also like to see DHP’s Cyrano, but don’t let me get sidetracked). We didn’t go out for drinks after because it was a Monday and we were really tired, and I’m just as glad, because I wanted to have my mind to myself on the way home. Think about certain moves and gestures, and phrases, and even costume pieces and all the things Williams was trying to say as he wrote and rewrote and rewrote. I realized the other day that since Williams was born in 1911, even if he hadn’t left us so suddenly and freakishly in ’83, he probably still wouldn’t be alive today. Well, he’d be 102.  Now I’m on the train to Philadelphia. But on that particular Monday a week ago, I was thinking about how satisfying the Williams play was in one way, and how satisfying a piece I’d seen two nights before had been in a completely different way. I’m talking about “Manna-Hata,” by Barry Rowell, which was presented by Peculiar Works Project in the upper regions of the James A. Farley Post Office. They had me at “partially gutted & abandoned upper floors of an old building.” And in the soon-to-be-destroyed/transformed space (it’s going to be a train station!) a company of 20 actors performed a very personal & deeply-felt history of the island that is still the center of the universe for many. (I, of course, moved to a borough in 1994). Still, it’s where I came when I came here, for things like theater and brilliant, crazy people who will put on a site-specific show in a marble building and say: hell yes, we can do shit like this in 2013 in what is either the end days of the American Republic, or a time when something new (which could be good or bad) is about to happen. I mean, even if you’re in the End Days, are you just supposed to wait for something bad to happen, or are you supposed to comment on what you see, and make people think a little bit, or laugh, or cry or walk while sweating past frosted glass doors and really nice sconces and molding? It’s been 300-plus years of power brokers and the people they want to break, businessmen who wipe out populations of natives, and crowds and mobs and riots where oppressed people get killed, and kill each other. And somewhere in there, little holes & corners where people drink and dream and write poems and plays. How can you not be thrilled all over again when Everett Quinton dances up and down a hall, wrapping peoples’ wrists in “caution” tape, Walt Whitman leads you through the miasma of history, and there’s Jane Jacobs singing, and Shirley Chisholm running for president, and a Lenni Lenape Indian reminding us who was there before before before. As long as we have people that smart and irreverent both fictional and real, I’ll still bet on us, despite the odds. And, of course, there are people who will find a way to produce a Tennessee Williams play that closed in a few days on Broadway in the 1970s and convince one of our great actors to come back to Manhattan and torment/comfort her brother/playwright to our edification and delight and soul’s satisfaction. The train is leaving Baltimore now.  I’ve been thinking these fond thoughts about New York from some 200 miles to the south, having attended the last performance “Grieving for Genevieve” in Laurel, MD. I’ve been fortunate enough to have had a fair amount of productions for an American playwright (a lot of which I’ve produced myself), so I can look back and say that this was the most fully-realized, best produced version of my work I’ve had a chance to see, some 200 miles from home – though in the same soil where the play grew. While I often bitch about the class system in American theater, I think it took someone with a similar background to mine, as in, having attended the same school, knowing the neighborhoods I was writing about, who the people were in the family I created, who is also a serious, rigorous artist, to create the production that I found so satisfying. In Deb Randall I found a sister (I have 3 blood sisters, but there’s always room for another sister of the soul). She’s doing all the stuff I was just ranting about in her own backyard. I got out of there and pontificate from NYC. She lives in Laurel and has made art there, producing 44 new plays. She’s certainly put in the work, and the time, and paid the price. And now she gets to call the shots, which include putting on a difficult, dark, funny play with four very loud women in her space, and literally taking the lead in getting it done. It seems to have been raining all spring. Dark clouds are always on the horizon. And what can we do but point out the obvious and if we are fortunate enough in these parlous times to actually have a job and a place to live, to throw our support, whatever we have, to someone with a good idea or a sense of justice, or march in a parade and say “I am here” or maybe get on another bus and do something sensible like register people to vote. My knees aren’t what they used to be (though I was never all that fast), and I can’t really close down bars anymore (except on some nights), but I’d like to think that my vision hasn’t faded. In fact, sometimes it’s kind of sharp.  Torrential rains left calf-deep puddles at the intersection of 42nd St. & 8th Ave. on Monday afternoon, and for a while everyone who came into the lobby of Playwrights Horizons just dripped for a bit. I squish-squished down the stairs to the restroom where several of us tried to pat our exposed parts dry with paper towels, then squish-squished back up for this year’s iteration of the lovely Lilly Awards: the day when the women playwrights honor their own and anyone else they feel like honoring. The brainchild of playwright/activists Julia Jordan, Marsha Norman & Teresa Rebeck (pictured above), the Lillies were invented to acknowledge people whose work was consistently overlooked; to right a wrong; to say, “thank you, you rock” to people who make going to the theater worthwhile. And as the awards have moved from their infancy to toddlerhood, they are taking off running, with a swagger, no less, with a character, a style, and panache of their own. They no longer exist as a reaction, but as their own ecosystem, and an annual fete that’s a loud celebration. I sat, a small puddle collecting underneath my seat (from the rain!) closer to stage right, and waited to see who’d be sitting in the semi-circle of chairs onstage, admired the massive bouquets of lilies at either end of the chairs, and waved at and chatted with nearby friends. The auditorium had looked a bit sparse as we approached the 6 o’clock start, but suddenly blossomed to capacity with damp, happy people. Then the chairs on the stage filled in, and Teresa welcomed us, and handed us over to Lisa Kron for the Benediction. Lisa is a great American playwright & performer, but she could totally have a side career as a toastmaster. If you’ve ever seen her emcee an event, or give a speech, you won’t forget it, and probably find yourself quoting it the next day. She promised us a moment of despair, some crankiness, and that she would end on a positive note, and delivered on all counts, reminiscing about her college days in which she was deemed a “character actress” which, she said, is code for “lesbian.” Then she came to NYC and recalled seeing the Split Britches company (pictured below): Peggy Shaw, Lois Weaver and Deb Margolin as a moment when her life “pivoted” in a direction it’s followed ever since, and she urged the assembled to challenge institutional thinking, and received wisdom, predicted that one day she might call someone a “dildo,” and concluded with: “Welcome to the Lillies, Amen!” Julia Jordan gave a brief history of the awards, and the progress in getting mainstream theaters to produce plays written by women. It’s up to around 30%, she reported, though statistics like that, I will point out, are but the tip of the iceberg, and rarely include the huge amount of work by women done by independent theaters and solo artists. As someone whose work, and the work of most of my friends is produced mostly in independent venues (and frequently self-produced), I appreciate & hope that the rising tide will lift all the boats, but in my world, parity is seen far more often than it is further uptown. Peggy Shaw has never made it to Broadway, but she’s one of the most important and influential artists in American solo and independent theater. Lisa Kron saw her perform at WOW, which still exists, and still incubates new work by women, as do spaces like La Mama (which was mentioned at the Lillies) and Dixon Place and HERE, also founded & run by women (Ellie Covan and Kristin Marting). I’m just saying that looking downtown & across the river yields a garden of wildflowers that complements the Lillies. Marsha Norman reported that the Lillies are increasing their reach (and grasp) by sponsoring readings of new work, and in this, their fourth year giving out prizes that are “not just medals.” Then she recounted how, since their founding, many people have helpfully pointed out that Lillian Hellman (the Lilly for whom the awards are named) “didn’t like women,” and indeed there is a famous quote in which Hellman said she was a playwright and a woman, but not a woman playwright. This led to a recurring theme of the event…women talking about how isolating it was to be the only woman in a room full of writers, and comparisons to dogs (used as a metaphor more than once), and led to a goal of the ceremony: Not to apologize for, but to celebrate Lillian Hellman (pictured below).  Playwright Neena Beeber came to the stage to present Jessica Hecht the Greta Garbo Award in Acting. Hecht spoke movingly from the point of view of an actor who wants to work with a playwright again and again, and sometimes must wait years between roles before getting a chance to return to collaborate with a fellow artist. Then actor Terry Kinney, natty in a 3-piece suit and cap, with a lovely blue tie ascended the stage to speak about Lois Smith (pictured above) with great affection and respect, and to present her with a Lifetime Achievement Award for acting. Smith appeared to be taken completely by surprise by the award, but with the aplomb of a great actress (and ordained minister!) she thanked the Lillies and remarked that sometimes the greatest life lesson is “just paying attention.” And she complimented the organizers for “bringing about the change they described.” Composer/performer/percussionist/sound designer David Van TIghem came to the podium and fooled around with the microphone, because he was there to present the first Seriously Stunning Sound Design award to Jill du Boff. The Lillies have made it a practice to honor the women in the technical, production and management aspects of theater, and this kind of openness, it seems to me, is one of the differences between the closed ecosystem that represents so many awards, and is the difference between “congratulations to us” and “congratulations to us all.”  Sarah Ruhl (pictured above, with Paula Vogel), who won the very first Lilly, was then called to the stage to present the latest one to Paula Vogel. She cited just some of Vogel’s achievements, her activism and generosity, told us how she has taught and inspired so many playwrights, and presented her friend and mentor with the beribboned Lilly medal. Vogel addressed Marsha Norman as her own inspiration, for letting her know “that a woman could open the door, AND leave it open for the next one to come through.” She said she feels the theater has become more enriched and deeper because “we’ve learned to love each other” and that her own life has been profoundly changed by the women and men in her workshops, and how much she has learned from their “profound journeys.” Then Mandy Greenfield of the Manhattan Theatre Club presented the next Lilly to Julie Crosby, artistic director of The Women’s Project & Productions, and Crosby spent a few moments talking about the renaissance of the company, both from an artistic and management standpoint; telling us that in its 35th anniversary season, the theater is “solvent” and that Time/Warner has committed $10,000 per lab artist for their playwrights and directors’ labs, and that Mayor Bloomberg has also become a sponsor. She told us that 84% of the Project’s income goes back to artists. Which is a huge institutional achievement, and here I am the fly in the ointment, but I will point out that with that kind of support, the Women’s Project should drop the $20 fee it charges to APPLY to its playwrights lab. The fee applies a de facto penalty on women who start out in the American economy making less than men, who may have crushing student loan debt, or a family to support, or who just aren’t lucky enough to have been born middle class, or have somehow lost that status. I’ve had email exchanges with the people who run the program, in which the responses run along the lines of what you always hear when you argue against charging a playwright a fee to have her work read: well, we have administrative costs. We have to pay the screeners. This is only a fraction of what it costs to run the program… And as someone who’s worked both in the administrative and receiving end of the non-profit arts, and written plenty of grant proposals, my response is: it’s not the playwrights’ responsibility to fund a program that’s there to develop playwrights for a company that has a mission to develop new work. Like the lottery, submission fees are the equivalent of a “poor people’s tax.” End of (essential) digression.  Marsha Norman, with great pride & joy in her former student, presented the next Lilly, the “Welcome to the World” award to Laura Marx, whose play “Bethany,” presented by The Women’s Project, was a much remarked-upon and well-received debut production for her. The outstanding director Leigh Silverman came up to present a Lilly to Tanya Barfield (both pictured above), for her most recent work, the critically acclaimed “The Call,” which opened on Broadway this spring. The award was fittingly titled: “The Hang in There, It’s the Middle of Your Career, We Need More of Your Plays” award, and was accompanied by one of the “surprises” promised by the organizers. Teresa Rebeck announced that she’d been approached by producer Stacy Mindich, who wanted to create a commission for a woman playwright. And while Barfield was still standing there, they gave her a a $25,000 commission for her next play. Barfield was overcome with emotion, and the playwright said a few deeply-felt words about her life as a playwright, which includes working a full-time job and raising children, and how much this means to her.  Lisa Kron then asked someone to hand her her wallet…and proceeded to present the next Lilly to director Lear de BIssonet, for her direction of Brecht’s “The Good Person of Szechuan,” which had an ecstatic, sold-out run at La Mama earlier this year, and will move to the Public this fall. Then came the award that’s become a highlight of the event, which answers the question: “Who is this year’s Miss Lilly?” And the answer was Garry Garrison, director of Creative Affairs for the Dramatists Guild, who donned the traditional sash & tiara, received a bouquet, and was proclaimed an “honorary woman” for his efforts. Then another surprise hit the stage in the form of Cusi Cram, who announced that the Lillies are joining forces with the new prize for women playwrights: the Leah Ryan Fund for Emerging Women Writers. The prize, which is now up to $1,000 and a staged reading of the selected work, was awarded to Jiehae Park, for her play, “Hannah and the Dread Gazebo,” which had its reading on June 4 at Primary Stages.  The Lillies then invented themselves again by awarding a special prize to Denise Scott Brown (pictured above), a legendary 81-year-old architect, and husband of the Pritzker Award-winning Robert Venturi, her design partner. In 1991, the Pritzker, the top award for architecture, was given to Venturi alone, though he and Scott Brown had been partners in every way as architects. Scott Brown’s deliberate exclusion from the prize recently prompted students at Harvard’s School of Design to start an online petition to recognize her for the work she did in partnership with her husband. The petition now has over 13,000 signatures, which Scott Brown noted is “a lot for architecture.” (It’s a lot for theater, too). Scott Brown then proceeded to give an eloquent talk that’s worthy of a blog post of its own; she immediately connected the treatment she’d received in her career with the “dispossession” that is often felt by women playwrights; she spoke of growing up with an architect for a mother, and how she spent the early part of her career shocked to find out that she was one of the few women in the rooms full of architects. She even wrote an article called “On Sexism and the Star System in Architecture.” She has always gone her own way, she said, and the rewards have been “ecstasy, and my own self-respect.”  The final award of the program was to another kind of architect: to the woman who created one of the most influential and valuable awards for women playwrights. When Mimi Kilgore (pictured above) lost her sister, Susan Smith Blackburn, she created a Prize in Susan’s honor, which is now given annually to recognize women “who have written works of outstanding quality for the English-speaking theatre,” and which awards $50,000 annually to the Finalists: $25,000 for the top prize, and $25 each to the finalists. In addition, the Winner receives a signed and numbered Willem de Kooning print made especially for the award. The award was presented to Kilgore by her son, Alex (also pictured), who spoke eloquently of his mother’s dedication to plays written by women, and when she accepted the medal, Kilgore said the award has “given my life a purpose and a strong sense of direction.” Then all the women in the audience who’d won the prize, been finalists, or served on the board were asked to join the Kilgores onstage, and the amount, range, and diversity of the talent was breathtaking, and the perfect final image to take away from the celebration. As we slowly made our way across the street for the afterparty, I thought of the work that has moved me recently, and how much of it was made possible by the long walk uphill that so many women and men have taken, that’s still going on, that one day may end at a level playing field. In the last month (which included a stint at the International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival), I’ve been privileged to see new work from Vickey Curtis, a wonderful Irish playwright & director; the Flux Theatre production of Johnna Adams’s “Sans Merci”; an outstanding solo play, “No Need for Seduction,” written & performed by Victoria Libertore, with a commission from Dixon Place; Mariah McCarthy’s site-specific “Mrs. Mayfield’s Fifth-Grade Class 20th Reunion” produced by Caps Lock Theatre; and the latest version of “The F*cking World According to Molly,” a solo show created by Andrea Alton at the Terranova Collective’s Solo Nova Festival. This weekend, I'm off to the opening of my play, "Grieving for Genevieve" at the Venus Play Shack in Laurel, MD, an independent thatre that's the brain & love child of Deb Randall...one of the many women who have spent their careers making it possible for women theater artists to have a place, not just in New York, not just in the institutional, mainstream theatre, but in every city, town and village where there's someone willing to look at an empty space and see a stage, stay up nights writing grants for the local arts council, build an audience that knows and wants more work from women. That put me in mind of people like Staci Swedeen and her Flying Anvil Theater in Knoxville, Dewey Scott-Wiley & Larry Hembree, with Trustus in Columbia, SC, Marj O'Neill Butler and The Women's Theatre Project in Florida..and so many more, more than I could name, which is a good thing. And I won't ever stop trying to find them and thank them (and, of course, send them my work). We are the Lillies of the Field: see how they grow; we do toil and spin, and we are all the better for it. I was in freakin' Dublin again, my home-away-from-home, representing NYC for Emerging Artists Theatre, with my play, "That's Her Way," at the International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival (for the fourth time). And of course I blogged about it here:

http://eatinireland.blogspot.ie/ ...and then we came home! “When I was a little girl, there was this wonderful show on TV.” That’s the first line of my play, “The Adventures of…” As a playwright, it’s taken me downtown, midtown, Provincetown (3 times) and to Dublin, Ireland. It’s never had the same cast for more than one production, a streak that remains unbroken in 2013. Last Wednesday, two days before the show was to open (again) in Provincetown, I got an email with the news that our leading lady had a family emergency. And I would be going on in her place. After thinking about it for a few seconds, I realized it was the best solution. I wrote the play, I’ve seen it more than anyone else, and the character is essentially an adolescent and adult version of me. As Tina Howe says: “It’s all true, but none of it happened.” My play had taken me back onstage.  Will Clark and Nick Lazzaro, in the EATfest production. To begin well before the beginning, I came to New York to act. After a brief stint at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, I was not asked back. I kept up with acting classes, and made the odd appearance in a showcase or two, and in summer stock. I was determined to stay in New York, and find a place in the theater and started fumbling toward what’s become a body of work as a playwright. Fast forward a number of years, and I’m doing my second 24-hour play festival at Wings Theatre. I liked the horror and excitement of it so much the first time that when they asked me back again, I said yes. We followed a standard drill: you pull things like settings, and actors and director out of a hat, and have words or phrases you must incorporate into the text. I ended up with: birthday cake, obstinate, and gymnastics; 3 actors, one of whom was my summer stock buddy, who’d since been in one of my full-lengths; a director I knew was quite good; and a setting: ATLANTIS, 1 MILLION YEARS, BC! (THANKS, Peter Bloch). Oh, and we also had to mention Clay Aiken. I muttered to myself on the train, pulling up, then tossing aside, ideas for plots, characters, how the hell to show Atlantis…briefly considering setting the whole thing underwater…trusting that I would get the idea I needed by the time I got home. Back when I was a sportswriter, I’d walk into the newsroom after a game, take a look at the clock, and know that by deadline, I’d have a story. It didn’t block me, rather it gave me the confidence to begin, because I knew I’d be done in time. At a certain point on the walk to my apartment, just as my building came into sight, I got the first line, and where it fit, and the idea for the rest of the play, and for the characters in it. I got home, I wrote it. When you’re doing a 24-hour play, you have to write with your id, rather than anything above it. Go deep, go personal, go mad. I finished it and had it at the theater by 10am (with mention of Clay Aiken in a totally organic way). I handed the scripts to my director and leading lady…but the other two guys in the cast were nowhere to be found. (Later we’d learn that…well, I forgot why they didn’t show up. What mattered is that they didn’t. I remember their names to this day). We drafted an actor from another play, and everyone got on the phone to see if we could round up a third. We briefly discussed me going on in the third part, which I discouraged. I went to the church across the street and lit a candle. And when I came back, one of the producers had found a guy in Jackson Heights.  Jamie Heinlein, Jason Alan Griffin and Hunter Gilmore in the Dublin production. The cast rehearsed all day, and I asked the director if we could go on last, so people would have more time to learn their lines. And…they did it. The audience loved it, and laughed so hard at the Clay Aiken reference that the actors had to hold. I knew I’d written a decent play, possibly one of the better things I’ve written. This unnerves me, because it was written in a blinding flash, in such a random manner. But I’ll take it. And hope to write something as good or better that’s…longer. I did a little tweaking and submitted it to Emerging Artists Theatre and it was accepted for an EATfest…with two out of three new actors. I submitted it to the Dublin Gay Theatre Festival in tandem with a piece by J. Stephen Brantley, in part because he had two men who could double in the male roles in my piece. We were accepted, and went to Dublin with two new actors, and the original leading lady.  Mark Finley, Jamie Heinlein and Lee Kaplan in the Women's Theater Festival production in Provincetown. I applied to the Universal Theatre Festival in Provincetown, and we were accepted, but our leading man had moved away, so we picked up another new actor. We were asked to come back the next fall, and this time, we had to bring along a new juvenile. The play was picked up by a theatre in San Francisco, and a friend of mine who went to see it said it was done very well; it’s on YouTube now. We were invited back to Provincetown for the final Universal Theatre Festival, a “best of,” and…we needed a new actor. I remembered the guy who came in from Jackson Heights for the first performance. He was available, and we were good to go. And then…I was in the mix. I can certainly be in front of people; I host a reading series, and appear on panels, and read my own work at the drop of a hat. But I haven’t set foot onstage as someone else since Ed Valentine’s “Women Behind the Bush,” in which I was a homicidal society matron (with one line), that we did all over town one summer. I printed out the script and highlighted it and started trying to learn it on the subway home. And in the car on the way up. I got a wonderful note from one of the other actors going up (who was taking the other part played by the actor who had the emergency). It was sweet and supportive, and she said she’d sit in for me at tech and not to worry, everyone had my back. About halfway to Provincetown, my wife realized that we were opening that night (she’d thought it was Saturday, and wondered why I was so frantic). We got there midafternoon and I rehearsed with the guys for about an hour, then went to find something to eat (not an easy thing in Provincetown on a January afternoon). I’d bought a couple pieces to wear as my costume, and accessorized a bit. I had the cut-down sides in my notebook (a handy prop I’d thoughtfully written in the original script for just such a purpose), but I didn’t need to refer to it. There was no way I could, or would, imitate Jamie Heinlein, the real Maggie. Instead, I took a deep breath, and looked at the audience, and just tried to live for a few moments, truthfully and loud enough to be heard, on the stage, with my own words. If I did it right, it would be enough. It was.  Memo, me, and Mark Finley at the Universal Theater Festival, Provincetown, Jan. 2013 I was very tired when it was over…and remembered I had to do it two more times. I was surprised how quickly the routine of going to theater early, putting on costume and makeup, and getting ready came back. Waiting backstage with the other actors, warming up and listening to the other plays, and eating fudge. I think I might have said “yes” to the whole thing because of the large pan of fudge I knew was backstage. Then it was over, and I could take off the red hi-tops I’d bought for the character, and put them on as myself when the weather gets warmer. The festival evaporates quickly…the out-of-towners have to drive a long way that night. There's no lingering over good-byes, or marveling over what we’d done. We were all on our way within minutes of the final bow. My wife and I stayed over one more night in Provincetown, and drove back the next day, still tired, relaxed, and tearing up as we listened to the President’s inaugural address on the radio. I have always thought that play could be longer. Whenever we rehearse it, I think of the ways it could be expanded, maybe even into a full-length. And having played it, I learned new things about it (and the writer). It hit me harder than ever that I want to expand this one. I know where I’d put the new scenes and what should happen when. If I do this, as I suspect I might, I promise, I will never, ever, go onstage in it. Acting is HARD.  I had to choose between being with my people last night and being with my people. This is what happens when you wear too many hats. What I mean is that there were I was invited to two awards ceremonies. One was the Lammies, the Lambda Literary Awards, the annual celebration of the best literature in the GLBT community. I was a judge in one category, a nominee in another. But in the same city, at the same time, there were also the Lilly Awards: the third annual celebration of women playwrights, by women playwrights, that honors our own, and the people who love us. I am a woman, a writer, a playwright, a queer person (in so many ways it’s multi-dimensional). And it’s become clear to me over the years that such distinctions are specious and no one has the right to ask you to define yourself or put those categories in an order. You might as well say: I’m a little finger. I’m a pancreas. It’s impossible. They were honoring one of the people I love most in the world at the Lilly Awards, so the decision was easy: Playwrights Horizons, 42nd St., with bells on, for Tina Howe.  Theresa Rebeck, Julia Jordan & Marsha Norman. As I took my place in the auditorium, next to a playwright we’ve decided is my long-lost cousin, I looked around and saw many people I knew: people I’d met through Tina; writers whose work I’d discovered and fallen in love with and just walked up to; people from up North and down South, and on the Internet. Not so many from Downtown, but I carry that particular state of mind with me wherever I go. We Independents represent whether we’re in a church basement with a pole in the middle of the stage, or in the ballroom of the Mandarin Oriental listening to Chita Rivera and Liza Minnelli honor John Kander (where we’d been the night before, because we won tickets to the Dramatists Guild gala). Tim Sanford, Artistic Director of Playwrights Horizons, resplendent in his “Miss Lilly” sash, an honor accorded to brothers who are also sisters, remarked that he is SO glad that The Lilly Awards are now a “thing.” He welcomed us, and introduced the divine Estelle Parsons to give the Invocation. Ms. Parsons spoke of her childhood (in the late ‘30s), discovering her voice in community theater, run as so many were, by a woman with intelligence and taste, who wanted more than the role prescribed to her by society at the time. Parsons, who would be honored later, finished with a rousing “Onward!” Then the founders: playwrights Theresa Rebeck, Marsha Norman and Julia Jordan welcomed us, and reminded us that the reason they’d called us all together again was that just three years ago, they’d watched as awards season left the station with no women on board…and they’d decided to throw their own party, and created the Committee for the Recognition of Outstanding Women in Theater. As my shrink says to me each time I leave him: “Remember, Kathleen, living well really IS the best revenge.” There was a delicious tension in the air as the women spoke of the need for self-recognition and celebration. The adjective “angry” was batted around, like a balloon, or a badge of honor. I’ve found that the word “angry,” depending on who is applying it, is often used as a weapon against someone who has a legitimate concern…or by someone who is frightened of what’s being said or asked.  David Ives, Miss Lilly of 2012. There were a total of 10 awards given, for writing, directing, acting, design, and all around awesomeness. (I’m not sure that’s an actual category; if it’s not, it should be). Joyce Ketay led off presenting the first Lilly, for directing to Diane Paulus, whose long resume includes the Broadway productions of “Porgy & Bess” and “Hair,” and who is the artistic director of A.R.T. Paulus accepted with alacrity (because she had to go off to a fundraiser for her own theater) and invited the women present to send her their plays, bring her projects they want to create or direct. David Ives then came onstage to present the acting award to the divine (an actual goddess in his play, “Venus in Fur,”) Nina Arianda. The multi-tasking Arianda, who was scheduled to perform for the President in a few hours, also took the time to speak movingly of her parents, especially her mother, as well as the writer who created the character she brought to life. And she also stuck around to present this year’s “Miss Lilly” award to Ives: complete with red silk sash, bouquet of flowers, and tiara, which Ives wore for the rest of the evening. Because that’s the kind of guy who is worthy of the title “Miss Lilly.” Tonya Pinkins then came to the stage to present a writing Lilly to Katori Hall, whose “The Mountaintop” had a successful run on Broadway last season (after its Olivier Award-winning run in London), and whose “Hurt Village” (starring Pinkins) was also seen at the Signature. Hall showed both gratitude and vigilance, reminding the audience: “We still have so much work to do.” Director Trip Cullman presented the next writing award to Leslye Headland, who is about to make her directorial debut with the film of her play, “Bachelorette.” (and also wrote this season’s “Assistance.”) Headland talked about once having had a fear of writing, and urged everyone to get over it…and she spoke movingly of Wendy Wasserstein as a mentor and friend. Acclaimed set designer Louisa Thompson presented the next award to Sarah Benson, artistic director of Soho Rep, whose award-winning work has included a production of Sarah Kane’s “Blasted” and new works by such wonderful playwrights as Annie Baker and Young Jean Lee. Benson was giving birth (pretty much) last year when she was first offered the award, and came back this year to talk about both artistry and motherhood. It was a theme mentioned by several of the women presenting and receiving awards: how they had been told that women “stepped away” when they had children, and couldn’t keep up their artistic careers…and then they told stories about how they’d done it (with the support of other artists, and also by multitasking such functions as tech rehearsals and breastfeeding. Marsha Norman presented the next award to Heidi Ettinger, whose many designs have shaped and enhanced Broadway plays, musicals, national tours, and operas. She designed the set for Norman’s “ ‘Night Mother,” and “The Secret Garden,” as well as the original production of Tina Howe’s “Painting Churches,” among many others. The next award was for musical acting, and went to Christin Milloti, and was presented to her by her co-star Lucas Pappaelias, who brought his guitar to the stage and serenaded her with a song of his own composition, which cited her various credits and had a chorus of “I get to party with Christin Milloti.” Christin broke the “f-word” barrier (and apologized profusely to her parents), and while it got used a time or two more, no one else really worked blue.  Tina and me. She gave me that necklace, of course. Then Robyn Goodman presented the Lifetime Achievement award to Tina Howe. She said “Tina Howe is her own most gorgeous creation,” and that she is a “great winged beauty,” which she is. As for me, I can’t begin to find words to say how much Tina has meant to me as a teacher and a friend. She’s someone who has touched so many lives…one by one…that there are generations of us whose hopes and views have been shaped by her kindness and wisdom. And Tina accepted the award in her inimitable fashion, citing her traumas as a schoolgirl, and her awakening to Ionesco, and how she put the “white gloves” on as a playwright, in order to be heard, while keeping her surreal, sublime vision close and visible to those who look. And Estelle Parsons was brought back to the podium for her award by Frances McDormand, who also knows a thing or two about making a playwright’s work sing. Then we all levitated and went across the street to the West Bank Café, where everyone mingled and consumed potent potables, and I’m so glad that the Lillies are a “thing” and not an institution, where we can repair to the bar after, and talk and get an eyeful of each other and tell stories, and pass the pizza and realize: we got it going on. And say “thank you.” To the women who’ve come this far, and the ones who are making it happen now, and pushing the ones after us into the future.  Wanamaker's Eagle Photo: M. McClellan for GPTMC When I was a little girl, my mother used to take me to John Wanamaker’s department store in downtown Philadelphia. It was a special treat to go down and see the great bronze eagle in the lobby, to eat at the Crystal Tearoom, and to stop by the founder’s office…left exactly as it was the day John Wanamaker died, behind a wall of glass, the day of his death outlined in red on the office calendar. To me, Wanamaker’s was one of the things that made Philadelphia a great city. A great city should have a fine department store, a world-class symphony orchestra, beautiful art museums, and a mediocre team in the National League.  Wanamaker's Mile. To Rogelio Martinez, “Wanamaker” was the name of a famous mile. That is, The Wanamaker Mile, a race for star runners in the annual Millrose Games at Madison Square Garden. Martinez ran track, and he knew that the Irish did well in it, especially Eamonn Coghlin, “Chairman of the Boards.” “I associated the Wanamaker name with Madison Square Garden,” Martinez said. “Only when I started to spend time in Philadelphia did I say to Terry (Arden Theatre artistic director Terrence J. Nolen): ‘tell me a little bit about the Eagle.’ That’s sort of how I arrived at it…via a long, circuitous route.”  'Wanamaker' playwright, Rogelio Martinez. Martinez, a NYC-based playwright, has had Philadelphia on his mind a lot lately as the author of “Wanamaker’s Pursuit,” a new play being presented at the Arcadia Stage by the Arden Theatre, directed by Terrence Nolen, as part of the Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts, currently in previews, and opening April 7, running until May 22. The title character in Martinez’s play is Nathan Wanamaker (played by Jürgen Hooper), a fictional character inspired by John Wanamaker’s grandson, John Wanamaker, Jr. Wanamaker Sr.’s son Rodman, actually did spend a great deal of time in Paris in the late 19th century. “When Rodman dies, the store gets passed to a trust,” Martinez recounted. “I was always interested in why it doesn’t go to the children. Oftentimes, third generations lose some interest in the family business.” Rodman Wanamaker took over the family business after his father’s death, but did not pass it on to his children (Wikipedia hints that Rodman’s only son, John, had “personal problems” which prevented his taking over the family business.) John, Jr. was known as “Captain John” after his service on General Pershing’s staff in World War I. Captain John died at the age of 45, in 1935. Martinez originally intended to write “a little bit” about John, imagining what the young man might have seen, who he would have met in Belle Epoque Paris. “I started writing a story about a young man going to Paris, learning to be a buyer,” the playwright said. “But what I was really writing about was Paris in 1911 (the heart of the time that gives PIFA its theme), with people like Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso.” This is when Stein and Picasso and other artists in their circle were becoming themselves, and before they became as visible to a wide range of people as they later did. “If you write about them at that time, we get to know who they are as they begin have an idea of who they are. This is the moment when their egos are beginning to blossom. By the time you get to the 1920s, their egos are in full bloom.” Among the relationships that he follows is that of Gertrude and her brother Leo Stein, which was beginning to fall apart, and it would eventually completely collapse. “I wanted to explore that aspect of it, a brother and sister coming to the end of their relationship,” Martinez explained. “And breaking up, in a sense. It was a sad breakup.” Martinez spent six or seven months doing the historical research on the piece, then another 3 months writing the play, and did rewrites over the course of another year. The play was commissioned as part of the Arden’s Independence Foundation New Play Showcase, and received additional support with an Edgerton Grant from the Theatre Communications Group, which allowed the production 2 additional weeks of rehearsal. So Martinez had the opportunity to bring his Nathan Wanamaker to Paris to meet and mingle with great artists on the verge. One of the major characters in the play is Paul Poiret (played by Wilbur Edwin Henry), a French designer whose influence on fashion made him one of the most important figures of his time; now he is more of a supporting character, not as well known, in today’s histories. “The idea is that this man was a name that’s now forgotten. It’s really interesting who history decides to remember and who it decides to forget. Leo Stein, as far as culturally, as far as being responsible for curating this art, is as powerful a force as Gertrude Stein,” Martinez said. “He wasn’t the artist that his sister was, but as far as having an eye for art, he was. But we’ve forgotten Leo. The Metropolitan Museum recently did a show on Paul Poiret’s fashions, so it’s not like we’ve forgotten him, but he’s not a name like Coco Chanel, who came in the 1920s, and knocked him off the map. Yet, in 1911, he was a rock star. He was it. He brought fashion into the modern era. So it’s interesting for me to see, and for audiences to see, who history chooses to remember and why.” “Why have we chosen to remember the Mona Lisa, when so much art was created in that period?” Martinez asked. (The theft of the Mona Lisa in 1911 is part of “Wanamaker’s Pursuit” and the subject of another PIFA play, “Art Lover” by Jules Tasca). “I don’t quite have an answer for that, and I don’t expect audiences to have an answer, but it’s interesting to contemplate the question, and at least each of the main characters has a different response to the paining that makes it personal to them. That’s what the Mona Lisa does…when we see it, we have a personal reaction to it, different from any other.” “Wanamaker’s Pursuit” also features Geneviève Perrier as Denise Poiret, Catharine K. Slusar as Gertrude Stein, David Bardeen as Leo Stein and Shawn Fagan in a variety of roles including Pablo Picasso. It's playing at the Arcadia Stage at the Arden Theatre, 40 N. 2nd St. Tickets are $20-$39 (student and senior discounts may be available). I’m very excited that the city of my birth, that is, the City of Brotherly Love, that is, where the Phillies play, is having an excellent international arts festival, and I’ve been invited to write about it. I’m certainly planning on grabbing one o’those cheap buses with the free Wi-Fi and making my way 99 miles south for some of the events. I had a chance to see a sneak preview here in NYC a few weeks ago, and have been going over the festival brochure and marking it up with “got to see” and “this looks good!” One of the highlights of the NYC preview was a monologue from Seth Rozin’s chamber musical “A Passing Wind.” Seth Rozin is also Artistic Director of InterAct Theater, one of the many vibrant indie theater companies in Philly, and one that is close to my heart because they have paid me for my work not once, but twice! (Stories I wrote were featured in their late, lamented series, “Writers Aloud.”) If you’re an American playwright, you know (or should know) that since 1988, InterAct’s mission has been to support the creation of new plays, and one which uses “theatre as a tool to foster positive social change in the school, the workplace and the community.” InterAct is currently in the midst of a 20-year (!) program, begun in 2007 that offers development awards and commissions for new plays each year. The playwrights who have received these awards/commissions thus far are some veteran folk (Lee Blessing) and outstanding new voices (Kara Lee Corthron) who now have a chance to create new plays with the support of a working theater. In Philadelphia. The monologue I saw from “A Passing Wind” featured actor Tim Moyer as Sigmund Freud; Freud narrates the play, but he’s not the character the title refers to, rather, that character is a man whose talents were a bit lower down. Once, Paris stood enthralled before (or behind) the man they called “Le Petomane” or “The Fartiste.” Joseph Pujol (1857-1945) was a man with a peculiar talent: he could suck water or air into his butt, and release it with precision control. As a performer, he usually did this with air, as I’m sure the water would have been quite messy. Pujol left his trade as a baker in Marseilles to take to the stage in 1887. With an air of confidence, he moved on to the big city (Paris), where he made it to the Show: The Moulin Rouge. Wikipedia notes that: “Some of the highlights of his stage act involved sound effects of cannon fire and thunderstorms, as well as playing "'O Sole Mio" and "La Marseillaise" on an ocarina through a rubber tube in his anus. He could also blow out a candle from several yards away. His audience included Edward, Prince of Wales, King Leopold II of the Belgians and Sigmund Freud.” (And from such entries as this are ideas for plays born…in fact, my friend & fellow playwright Charlie Schulman is working on an off-Broadway musical, a hit at NY Fringe a couple years back, called “The Fartiste” also about Pujol. But surely there is room in the American theatre for two plays about a man who took the advice “blow it out your ass” literally). There’s a YouTube video of Le Petomaine (which I've linked below) from a film made in the 1880s (which of course, sadly, doesn’t have a soundtrack). Along with the grossly wonderful premise of a man who made his living by farting, is the reality that The War to End All Wars (WW I, not the sequel), drove Pujol from the stage. He found that the horror of war “left unprecedented physical and psychological devastation in its wake,” according to the description of the play. And THAT’s where plays are born. Written and directed by Rozin, the production will feature Damon Kirsche, Ian Bedford, Maureen Torsney-Weir, Jered McLenigan, Peter Schmitz, Tim Moyer, Leah Walton and Laura Catlaw. Music direction and sound design by Daniel Perelstein; set and lighting design by Peter Whinnery; costume design by Anna Frangiosa; choreography by Karen Getz. It premieres April 7, running through April 16, at the Innovation Studio of the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, 300 S. Broad Street. Tickets are $15-$29, and available here. This interview is brought to you with the support of PIFA (Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts). If you liked the interview above and want to help ensure that PIFA becomes an annual event please Like their Facebook Page and Follow them on Twitter ! |

Kathleen W.

Writer, editor, curator, Ambassador of Love. Archives

May 2014

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed