Joseph Hallman agrees. When he was chosen to be Composer-in-Residence at the Rosenbach, Hallman says he thought: “if only this were a residency residency! They told me they were considering it for the future.” And he told them he’d come back for that.

Hallman, a Philadelphia born and educated composer, has worked with some of today's most talented musicians and artists. His recently completed series of chamber concerti were composed for members of the Philadelphia Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Pittsburgh Symphony, and Cleveland Orchestra. Hallman has also worked in the downtown New York music scene with the improv/experimental group ThingNY. He’s an adjunct faculty member at Drexel University, and Composer-in-Residence and Assistant Director of Festivals for the Traverse Arts Project.

De Acosta’s life and times were shaped by the theme of the festival: the artistic experimentation and uninhibited creativity of Paris in the early part of the 20th century. She was a lover of women at a time when such things were not spoken of, and she had an eye for talented artists and women of great beauty: her lovers included Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Eva le Gallienne, Isadora Duncan, among many others.

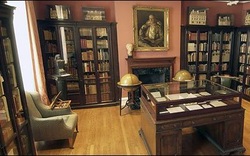

As he went to work, Hallman spent about 4 months in the archives, working with the research librarian and archivist, going through documents: de Acosta’s letters, her books, her plays, and sort of ephemera that she had collected and sold to the Rosenbachs before she died.

de Acosta’s older sister was famous in her own right for her beauty and influence on fashion and design, as well as her several marriages.

“Her sister was old enough that Mercedes looked up to her a lot, and wanted to be like her,” Hallman said. “She was a fashion icon; she was famous in her own way for being a socialite and they had a falling out, and it’s a sad thing, you can tell she aspired to be much like her sister.”

Hallman describes de Acosta’s relationship with Garbo as “the puppydog relationship, where Mercedes was sort of hounding her, and Garbo reciprocated at times, but not all the time, and not publicly.”

Hallman also noted that de Acosta “had her own way of telling things…you never know what the truth was. I think she had a way of accentuating the things that would make her look good, or make a situation look more dramatic. She was hyperbolic and self-aggrandizing, and I think that affected a lot of what she put out.”

This, of course, can be a boon to a biographer or adapter, as larger-than-life characters can leap most readily to artistic life.

“There’s the unrequited lover, that one was the hardest to write,” he said. “It’s got a series of episodes, and each of the episodes represents an emotional state that one might be in, frustrated longing, one where you’re the supplicant, submissive to the person’s will and whim, and no matter what, you’ll sing their praise. The second one is the one with the relationship with the sister; and the third is more stable relationship with Isadora Duncan. I wanted to create universal emotional tropes, more than a specific moment or person. Of course it’s about her, and you know these are based on her life, but I wanted to create these universal emotional themes I think anybody who’s ever been in love can relate to, can see or feel these things.”

As Hallman collected his research on the three central relationships, he decided that there would be a representative voice of Mercedes, sung by one singer. He passed along his research to his collaborator, Jessica Hornik, who created poems that Hallman would set to music.

“Most of the poems are in first person, and they’re not specific to any situation,” he explained. “They’re nostalgic and memory-laden, and they’re really beautiful on their own. Jessica is really a wonderful, wonderful poet. She’s done every vocal piece I’ve done except one. She’s a muse of mine. I’d send her recordings, clippings, pictures, all kinds of things, and she would send me stuff back.”

“The lesbian element is so there,” he said. “You have to think about these relationships happening at this time. And they had to be so secretive. You think of these things as being taboo, and not at all feasible, but they had them of course, and they happened under different guises, and it’s just amazing to see. It’s a great part of gay history to know about this. But at the same time, I didn’t want it to be ghettoized as a gay project alone. I wanted people to feel: these are two women in love, but it was bigger than them being two women. I wanted to do both of those things, be celebratory of gay history, but universal so that anybody could feel like: wow, I feel that, or I can understand those emotions.”

Hallman composed the pieces for the flute, cello, and harp of the Dolce Suono ensemble (flautist Mimi Stillman, cellist Yumi Kendall, and harpist Coline-Marie Orliac. Soprano Abigail Haynes Lennox will sing the songs.

Hallman says in composing the music, he was “influenced by music of that time, of the ‘20s, the sort of impressionist chanson and French art songs.”

In terms of the emotional qualities, Hallman described what he was going for: “The first movement has got so much in it, it is full of pathos and every conceivable emotion when you love someone more than you could ever love you. There’s unbridled joy at moments, unbearable depression at others.”

Hallman’s time in the archive will spark other work, he knows. “I had such a great time working in the archive: it’s like overload. You don’t know how to process it. I wrote a 20 minute piece and tried to talk about 60 years of a woman’s life and her love. It’s funny to think of these things and that was what was cool about it for me, seeing the people as living, breathing things, rather than someone sort of having written about them. Seeing their lives through their eyes was phenomenal.”

He hopes for the piece to continue to be performed and developed after its PIFA premiere.

“Every composer’s dream and desire is to have their piece performed more than once,” he said. “It’s frustrating to realize you may only get one performance; I don’t think that will be the case with this piece. It’s a strong piece and a strong group, and I think it has a good message.”

Ed note: Kathleen Warnock received financial compensation for this post from PIFA (Philadelphia International Festival of the Arts).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed